The Shackleton-Rowett Expedition

In September 1921, polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton left London aboard the Quest to begin his last expedition to Antarctica. Famously, he would never return. Shackleton’s death aboard the Quest while it was anchored in the harbour at South Georgia marked the end of the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration.

Today, Shackleton’s body is buried at South Georgia, and each year hundreds of people make the pilgrimage to stand at his grave. Many books have been written about Sir Ernest Shackleton, and the recent discovery of one of his previous expedition ships Endurance, made worldwide headlines. Other books have been written just about Shackleton’s final expedition on the Quest.

But what people don’t know is that on the Quest with Shackleton was a young Australian explorer, George Hubert Wilkins, who would be late knighted and known as Sir Hubert Wilkins. Throughout his life, Wilkins collected copies of his correspondence, reports and even souvenirs from the expeditions that he went on. During his time with the Quest, Wilkins wrote letters to his mother, reports for the British Museum and took photographs. Also, in the 1950s, when Sir Ernest Shackleton’s first biographer, Margery Fisher, was planning a book about him, Sir Hubert Wilkins wrote long letters to Fisher recalling what happened aboard the Quest, and the state of mind that Shackleton was in.

Unpublished Letters From Shackleton’s Quest

These letters and reports by Sir Hubert Wilkins are still in private hands and have never been published.

So, in a series of articles, I am going to reproduce extracts, and for the first time in over 100 years, give new insights into the last days of Sir Ernest Shackleton.

George Hubert, (later Sir Hubert) Wilkins, had just returned from his own expedition to Antarctica in the Southern Summer of 1920/21 and was back in London, when (on 7 August 1921) he wrote to his Mother on Shackleton-Rowett Expedition letterhead and outlined Shackleton’s original plans:

Dear Mother,

On arriving from America I finally decided to go with Sir Ernest Shackleton, although I do not know whether it would not have been better for me to have gone back with Mr Stefansson.

However I have accepted the appointment as Naturalist to the above expedition at a salary of 600 pounds a year and all expenses and according to our present programme I should be in Australia in less than a year’s time. The expedition’s boat does not intend calling at Australia, but will be spending some time in New Zealand and I hope to get time to come across and see you then. I daresay you have seen the details of the trip in the papers, but in case you have not, I will just give you an outline of it. We leave here in a boat which is 110 feet long with steam engines and sail, well equipped for scientific work, about 1 September. After calling at some port in France we go to the Savage Islands off the west coast of Africa, then to St Pauls Island on the Equator. These Islands are rather out of the way of ordinary ships and are very rarely visited. They are said to be very interesting, and we may find on them some new forms of bird and plant life. Trinidad is the next calling place.

We then visit the island of Tristan Da Cunha, which is some distance west of Cape Town, South Africa. A small British colony lives on this island and are visited very seldom, perhaps not more often that once in three years, and then only by some passing sailing boat driven out of its way. From Tristan Da Cunha we go to Gough Island, a place that has only been visited twice before so far as we know, and there we shall probably find some new and interesting things. This should bring us to some time in December and we shall then go to Cape Town to re-stock our ship with supplies and get mail. It is there that I hope to get some news from home for I have not had any except the calls about the money in New York, since my return. I will let you know the address to send to in Cape Town when I next write.

From Cape Town we shall go south towards the Antarctic, calling at the Marion Islands, which have not been landed on so far as we know, and this will no doubt prove an interesting field. We hope to reach the Antarctic barrier at a point known as Enderby Land, that was discovered over a hundred years ago and has not been visited since, and from here we will try and follow the coastline for about 1200 miles, covering an entirely new area. We shall be doing this during the Antarctic summer and when conditions will be quite comfortable, no darkness, and sunshine most of the time I expect, if it is like last summer I spent in the Antarctic. We will leave the Antarctic coastline a few hundred miles from where I spent last summer and go to the South Georgia Islands, where we will be again, some time in April, in touch with civilization.

From South Georgia we go to Bouvet Island, a place that is very little known, and then back to South America, to one of the ports there, probably Punta Arenas, where we will get mail and supplies about the end of May next year. We then go across the Pacific Ocean looking for two groups of islands that have been reported several times but not definitely located, and so far as we know, nobody has ever landed on them. We hope to find them on our way to New Zealand, where we expect to arrive some time in July. We shall restock again here and then set out for South Africa again and back to England, thus going round both the length and breadth of the Earth. It is exceptionally fine opportunity to visit most of the little known parts of the globe and to so some extremely useful work in collecting natural history information, and mapping these new and little known islands.

In August 1921, Wilkins seems wonderfully optimistic about Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ambitious plans. The optimism must not have lasted long, for a couple of days later Wilkins wrote in his notebook how, on meeting Frank Wild, the first thing Wild did was borrow money from him. Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Quest expedition was no sooner at sea, than it sailed into a storm. Wilkins commenced writing his detailed report for the British Museum, and already a tone of gloom seems to have descended on the crew.

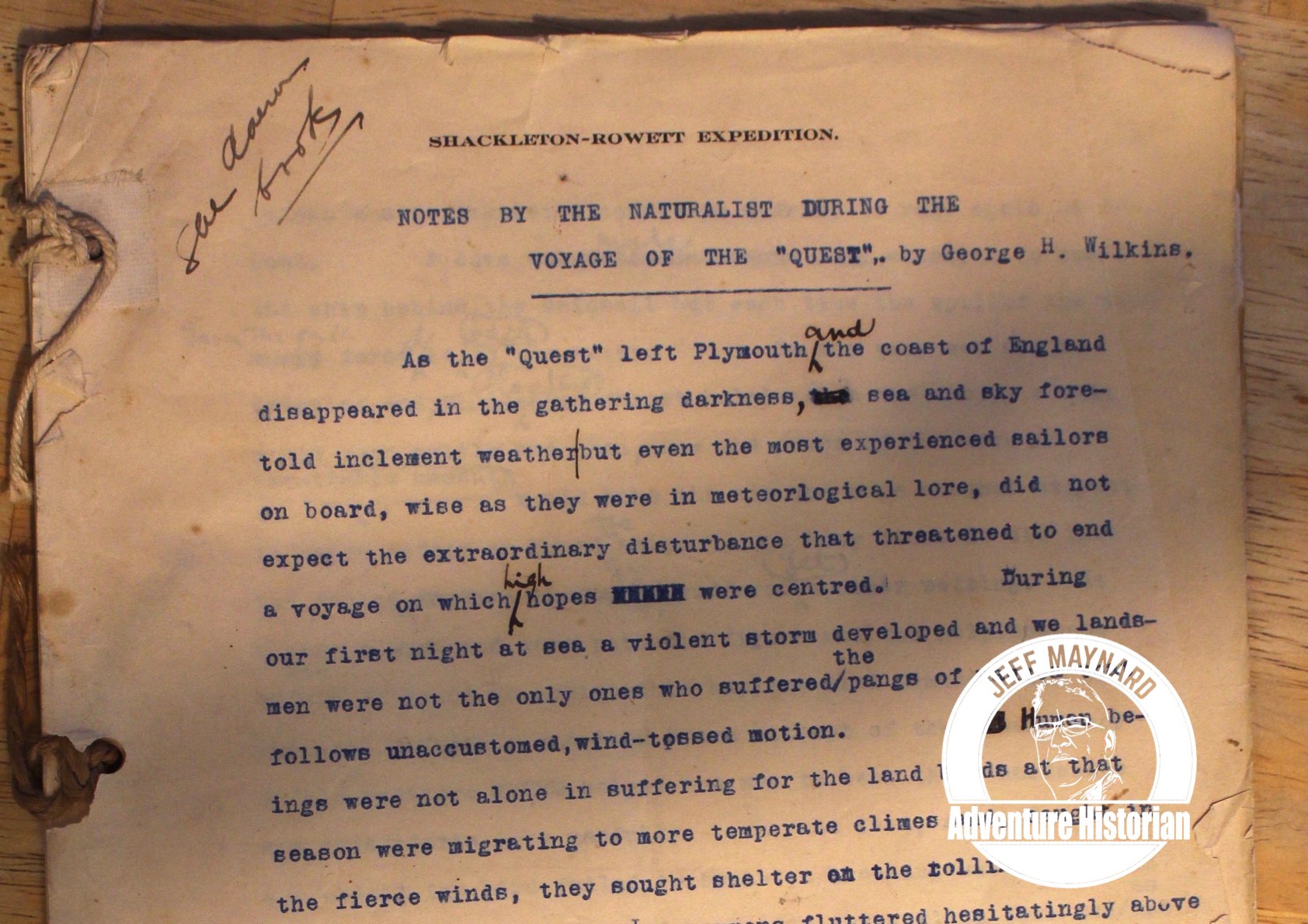

As the Quest left Plymouth and the coast of England disappeared in the gathering darkness, sea and sky foretold inclement weather, but even the most experienced sailors on board, wise as they were in meteorological lore, did not expect the extraordinary disturbance that threatened to end the voyage on which high hopes were centred. During our first night at sea a violent storm developed and we landsmen were not the only ones who suffered the pangs of nausea that follows unaccustomed, wind-tossed motion, for the land birds at that season were migrating to more temperate climes and, caught in the fierce winds, they sought shelter on the rolling boat. Larks, doves and little Jenny wrens fluttered hesitatingly above the topsail wondering if they dared seek rest on the swaying mast. With tired wings they dropped to a guy or stay, but the violent, jerky motion of the ship threatened to be a more difficult medium than the angry wind. Some of the birds more daring, or more tired perhaps, did alight on the yard arm and, nestling in the folds of the topsail, rested and preened their ruffled feathers. Others, caught in the down draught of the sail, were forced to the deck and remained there, less terrified by the nearness of man than of the elements. Several of the birds on deck were so exhausted that they did not attempt to escape from the hands of the sailors and were caught and closely examined. They were measured and colour notes taken, but a sympathy with fellow creatures in distress would not allow even an enthusiastic naturalist to take these birds for specimens. Food and water were placed before them and after a few hours’ rest they flew away to seek new fields in which to gladden the hearts of nature lovers in other countries.

The storm lasted several days and occasionally a bird would fly away for a few hours, only to return in a more exhausted condition seeking to rest again on the boat. A dove made many attempts to board the ship behind the mainsail, but each time the spill of the wind from the sail forced the dove to the water. It was very wet and bedraggled and, floating almost helpless on the choppy sea, it would rest a while and then, from the crest of the wave in a favourable moment would take to the air and make another attempt to reach safety on board ship. Many times it did this but, failing, suffered another wetting. It became a more and more pathetic figure and the helplessness of the men on board to assist this hapless bird dimmed their own physical suffering and each brave attempt of the poor little creature helped them to bear their hardships and discomforts more fully. At last, a beaten, pathetic object, the bird failed to breast a breaking wave and after a struggle it dropped back into the curling foam and was lost. It had been a game and plucky fight for life and with that example of courage and endurance, fighting to the last, we struggled on.

Six weeks after leaving London, Wilkins wrote to his Mother again. The mood of optimism had gone, and he was expressing his disappointment for the change in plans due to the repairs needed to the Quest, along with his observations of Shackleton.

Dear Mother,

Owing to the ship being so much out of repair, there is so much to do that it leaves us very little time for letter writing. We called at Madeira last week and I went into the country collecting birds, insects, plants, etc. and in consequence had no time to write any letters at all. We are going to coal at this island and then go on to St Pauls and South Trinidad and from there go onto Rio de Janeiro to repair engines and masts. This should really be done now, but we can’t afford to miss the islands and must make the ship do as she is for another month. The delay at Rio will probably be three weeks or a month and this will mean altering our programme, not reaching Cape Town until March or April next year instead of December of this year.

One can never tell on expeditions just what one can do ahead. You can only make plans as the opportunity occurs.

I am not very much impressed with Sir Ernest’s leadership. He is far less competent than Vilhaljmur Stefansson and not such a big-minded man. He cares only for newspaper notices and money, while Stefansson, besides that, does really want to do some scientific work.

We will have a very interesting trip in any case but I am rather disappointed in the change of programme in so far as it does not allow us to do much work in the Antarctic, which was my official interest.

Because of our delay in Rio I shall probably not hear from you for some months yet, but I hope you are all well and I trust that at the Cape I shall get some letters.\

Wilkins also took over from the photographer on board the Quest, who was constantly sea sick. He photographed life on board, and when the Quest arrived at South Georgia.

In his report to the British Museum, Wilkins pointed out that he had no shortage of glass bottles in which to collect specimens of plant and sea life. He simply collected the empty beer bottles of the crew, and assured the Museum that the crew gave him a steady supply.

To be continued…

Visit www.netfieldpublishing.com.au for the limited edition book The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins